Dianna West Lays Bare the Liberal Problem In the War on Terror

If we still valued our own men more than the enemy and the "civilians" they hide among - and now I'm talking about the war in Iraq - our tactics would be totally different, and, not incidentally, infinitely more successful. We would drop bombs on city blocks, for example, and not waste men in dangerous house-to-house searches. We would destroy enemy sanctuaries in Syria and Iran and not disarm "insurgents" at perilous checkpoints in hostile Iraqi strongholds.

In the 21st century, however, there is something that our society values more than our own lives - and more than the survival of civilization itself. That something may be described as the kind of moral superiority that comes from a good wallow in Abu Ghraib, Haditha, CIA interrogations or Guantanamo Bay. Morally superior people - Western elites - never "humiliate" prisoners, never kill civilians, never torture or incarcerate jihadists. Indeed, they would like to kill, I mean, prosecute, or at least tie the hands of, anyone who does. This, of course, only enhances their own moral superiority. But it doesn't win wars. And it won't save civilization.

I'm reminded of the cloud of smug arising from LA in South Park after the entire population buys Pius cars to assert their moral superiority on the issue of environmentalism.

Dianna West is thinking about a cloud of smug as well, as she continues:

Why not? Because such smugness masks a massive moral paralysis. The morally superior (read: paralyzed) don't really take sides, don't really believe one culture is qualitatively better or worse than the other. They don't even believe one culture is just plain different from the other.

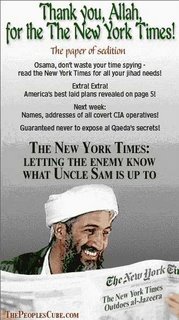

This is the same kind of extreme moral paralysis, or blind inability to take sides, which allows the NYTimes, for example, to publish details of the counterterrorism program currently in place.

But back to Dianna West:

Only in this atmosphere of politically correct and perpetually adolescent non-judgmentalism could anyone believe, for example, that compelling, forcing or torturing a jihadist terrorist to get information to save a city undermines our "values" in any way. It undermines nothing- except the jihad.

Do such tactics diminish our inviolate sanctimony? You bet. But so what? The alternative is to follow our precious rules and hope the barbarians will leave us alone, or, perhaps, not deal with us too harshly. Fond hope. Consider the 21st-century return of (I still can't quite believe it) beheadings. The first French Republic aside, who on God's modern green earth ever imagined a head being hacked off the human body before we were confronted with Islamic jihad? Civilization itself is forever dimmed — again.

The editorial board of the NYTimes, instead, wants to preserve itself in the cloud of smug, "unsullied" by facing up to the hard decisions and realities of warfare. They want to remain pristine.

By the way, I've often thought exactly the same thing as Dianna West. I'm glad she had the guts to put it into print in a newsaper.

From The People's Cube

Yet the only way for great nations to win small wars - wars in which modern democratic nations are fighting brutal terrorist regimes - is for there to be a clarity of purpose in the leadership. Obviously, in today's world, the leadership is only the political leadership, and does not, in any way, include the so-called cultural elite, which chooses to abstain, precisely, on the "messiness" of moral grounds.

Yagil Henkin, writing in Azure Magazine, comments more on the modern problem of Great Nations fighting and winning Small Wars:

We live today in an age of small wars. In contrast to the last World War, which ended six decades ago and encompassed dozens of nations, spanning continents and seas, the current age is characterized by a different kind of armed conflict. The primary enemy confronting countries is no longer other countries, but guerilla armies and terrorist organizations - armed groups whose power is measured not by the amount of force they can bring to the battlefield or by the quality of their weapons, but by their ability to wear down the other side and break its will to continue fighting...

[I]n a protracted conflict against a weaker but more determined opponent, the likelihood that a nation will lose is further increased when it is a democracy. Whereas non-democratic countries will often use extreme force against the weaker side even to the point of annihilating it or transferring or expelling entire populations, democratic countries, according to Merom, "are restricted by their domestic structure," which is why "they find it extremely difficult to escalate the level of violence and brutality to that which can secure victory." According to this view, the weakness of democracy stems from the influence of public opinion on the decisions of political leaders: The public generally frowns upon the use of overly violent means, and it does not have the patience for prolonged fighting. "The interaction of sensitivity to casualties, repugnance to brutal military behavior, and commitment to democratic life," says Merom, often leads democracies into a situation where they cannot or will not use enough force to ensure victory. By contrast, countries that are "less liberal and less democratic can be expected to encounter fewer and lesser domestic obstacles … when they fight brutally small wars."

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home